Introduction

The Washington State Ferries (WSF), the largest ferry system in the United States, traces its operational and philosophical roots to the innovative Black Ball Line, a pioneering 19th-century shipping enterprise. Established in 1817, the Black Ball Line revolutionized transatlantic transport by introducing scheduled sailings, a concept that reshaped global maritime commerce. This innovation laid the groundwork for modern ferry systems, including WSF, which continues to rely on public funding to serve millions annually. This article explores the historical significance of the Black Ball Line, its evolution into the Puget Sound Navigation Company, and its enduring influence on Washington’s ferry system, while addressing the financial and operational challenges of public subsidization today.

The Birth of Scheduled Sailings: The Black Ball Line

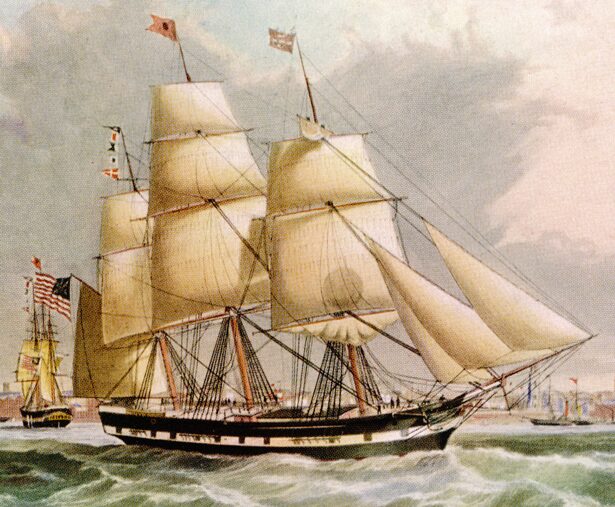

In the early 19th century, transatlantic shipping was notoriously unreliable, with vessels departing only when fully loaded, often causing delays of weeks. This unpredictability hindered trade and passenger travel. In October 1817, a group of New York merchants—Isaac Wright & Son, Francis Thompson, Benjamin Marshall, and Jeremiah Thompson—founded the Black Ball Line, introducing a radical concept: fixed sailing schedules. Named for its distinctive flag; a black ball on a red background, the line promised departures from New York on the 5th of each month and from Liverpool on the 1st, regardless of cargo capacity.

The Black Ball Line’s first vessel, the James Monroe, inaugurated this service on January 5, 1818, departing New York with eight passengers and a partial cargo of apples, flour, cotton, cranberries, hops, and wool. The ship reached Liverpool on February 2, 1818, in a respectable 28 days, despite challenging winter conditions. The return voyage, delayed by storm damage, highlighted the risks of early maritime travel but did not deter the line’s commitment to reliability. By 1818, the fleet included four ships: James Monroe, Pacific, Amity, and Courier, each around 400 tons, later joined by larger vessels like New York, Eagle, and Albion.

The Evening Post in 1817 praised the line’s commanders as “men of great experience and activity,” predicting that scheduled sailings would make the Black Ball Line a preferred choice for merchants. This proved true, as the line’s reliability attracted shippers willing to pay premium rates for guaranteed departures, elevating New York above Boston and Philadelphia as a premier port. By 1821, competitors like the Red Star Line and Swallowtail Line emerged, but the Black Ball Line remained the most iconic, operating for over 60 years until the rise of steamships in the late 19th century.

The Peabody Connection to the Black Ball Line

The Peabody family’s association with the Black Ball Line began with Enoch Peabody, a descendant of a prominent New England seafaring family. Born into a lineage of ship captains and merchants, Enoch was drawn to the maritime trade early in life. By the 1830s, he was captaining vessels for the Black Ball Line, leveraging his expertise to navigate the demanding North Atlantic routes. His role as a captain placed him at the heart of the line’s operations, earning him respect among the merchant community and deepening his connection to its innovative ethos.

Enoch’s ties to the Black Ball Line were cemented through his marriage to Cornelia Marshall on April 26, 1855. Cornelia was the daughter of Benjamin Marshall, one of the line’s original founders, whose vision for scheduled sailings had revolutionized shipping. This union linked Enoch not only to the line’s operational legacy but also to its founding family, embedding the Peabody name in its history. Enoch worked closely with Cornelia’s brothers, Benjamin Marshall’s sons, in managing Black Ball vessels, further solidifying his influence. Their third child, Charles E. Peabody, born on December 4, 1857, would later carry this legacy to the Pacific Northwest, extending the Black Ball Line’s principles to new frontiers.

Transition to the Pacific Northwest: The Alaska Steamship Company

The Black Ball Line’s legacy transcended the Atlantic through Charles E. Peabody, who bridged the family’s maritime heritage to the Pacific Northwest. After a brief stint as a Wall Street stockbroker, Charles was appointed a special agent for the U.S. Revenue Cutter Service in 1882, relocating to the West Coast at age 25. En route, he met Lilly Macaulay, daughter of Vancouver Island lumber magnate William J. Macaulay. Their marriage in 1891 and Charles’s business acumen led to partnerships in coal, logging, and banking in Port Townsend, Washington, where he also collaborated with Macaulay’s lumber operations in Chemainus, British Columbia.

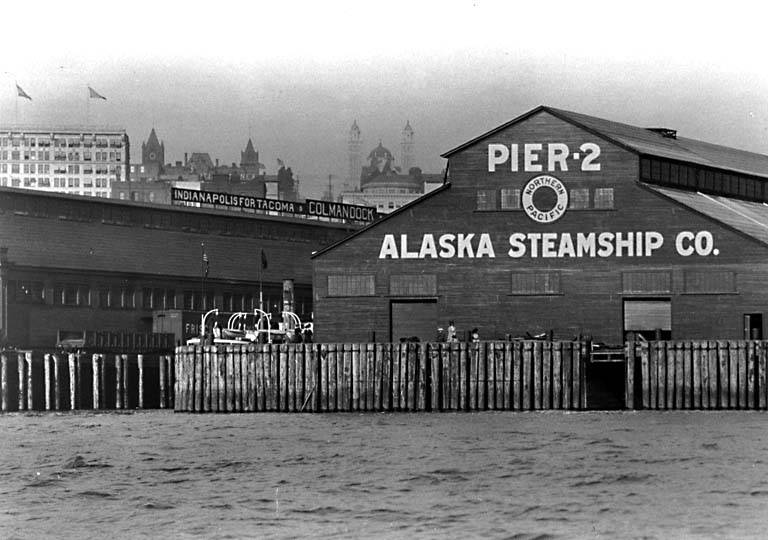

In 1894, Peabody, alongside Walter Oakes, George Roberts, Melville Nichols, George Lent, and Frank E. Burns, founded the Alaska Steamship Company, capitalizing on the Klondike Gold Rush of 1897. With $30,000 raised through stock sales, the company purchased the Willapa, a 140-foot steamer that flew the Black Ball flag, symbolizing its heritage. The Willapa competed directly with the Pacific Steamship Company, offering passenger and freight services from Puget Sound to Southeast Alaska. The gold rush fueled demand, and the company expanded its fleet to 67 vessels, transporting mining equipment, livestock, and passengers. By 1898, the Alaska Steamship Company formed the Puget Sound Navigation Company as a subsidiary to manage inland routes, leveraging smaller vessels as Alaska runs demanded larger ships.

Puget Sound Navigation Company: Dominating Inland Waters

The Puget Sound Navigation Company grew rapidly, acquiring controlling stock in the LaConner Trading & Transportation Company in 1903 for approximately $100,000. This consolidation brought 20 steamers under one management, including vessels like Majestic, Rosalie, Dolphin, and George E. Starr. Charles Peabody became president, with Joshua Green as vice president and Walter Oakes as secretary-treasurer. The company introduced innovative routes, such as the Port Townsend–Port Angeles–Victoria run, capitalizing on competitors’ focus on Alaska routes.

By 1908, the Puget Sound Navigation Company reorganized, increasing its capital stock from $500,000 to $1.5 million and relocating its terminal to Colman Dock in Seattle. The company adapted to emerging trends, notably the rise of automobile transport. In 1906, Captain William P. Thornton ferried the first automobile across Puget Sound on the State of Washington. To accommodate Charles Peabody’s personal touring car, crews improvised ramps and deflated tires to navigate low-clearance cargo decks, setting a precedent for auto-ferry conversions. By 1918, the company purchased and refitted the Bailey Gatzert to carry 30 automobiles, and in 1921, the Whatcom was converted into the City of Bremerton, designed specifically for auto transport.

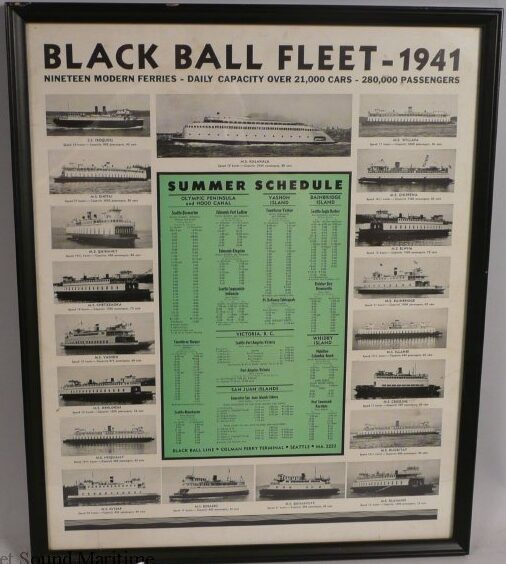

In 1926, following Charles Peabody’s death, his son Alexander Peabody assumed leadership, reinstating the Black Ball Line trade name and flag. By 1929, the Puget Sound Navigation Company, now commonly known as the Black Ball Line, dominated Puget Sound, outlasting competitors like the Kitsap County Transportation Company after a 1935 strike. The introduction of the Kalakala in 1935, a revolutionary Art Deco ferry built on the hull of the burned-out Peralta, marked a high point. Designed with input from Lilly Peabody for a “rounded” aesthetic, the Kalakala carried thousands daily during World War II, supporting the war effort with 450 daily sailings across 15 routes.

Challenges and Transition to Public Ownership

Post-World War II, rising labor costs and union demands strained the Puget Sound Navigation Company’s finances. In 1948, the company requested a 30% fare increase to cover higher wages, but the Washington State Highway Department denied it. In response, the company halted services, disrupting cross-sound travel. On December 30, 1950, Governor Arthur B. Langlie offered to purchase the Black Ball Line’s assets, including 16 ferries, 20 terminals, and related equipment, for the state. The $5 million deal, finalized in 1951, birthed the Washington State Ferries (WSF), with the state retaining five vessels and the Seattle–Victoria route for private operation.

WSF was initially intended as a temporary service until bridges could connect Puget Sound’s east and west shores. However, no bridges were built, and WSF became a permanent fixture, serving 17 million passengers and 8.9 million vehicles annually by 2022. The system’s financial model aimed for self-sufficiency through fares, but by the late 1990s, fare revenue covered only 65–66% of operating costs. Today, for the 2025–27 biennium, fares generate 57% of the $397.1 million annual operating budget, with the remaining 43% ($170.75 million) subsidized by state and federal funds. State contributions include $46.985 million annually for operations, while federal grants, primarily for capital projects, contribute an estimated $5 million annually to operations.

Modern Challenges and Public Perception

The transition to public ownership shifted the Black Ball Line’s legacy from private innovation to a publicly funded necessity. WSF faces ongoing challenges, including an aging fleet (15 of 26 needed vessels operational in 2025), staffing shortages, and deferred maintenance costing $270 million. Public funding, totaling $1.8 billion for the 2025–27 biennium (including $1.2 billion for hybrid-electric ferries and $288 million for terminal electrification), reflects the system’s economic importance to tourism, commerce, and labor.

Despite subsidies, public sentiment remains mixed. Riders often resist fare increases, yet expect reliable service, echoing complaints from the Black Ball era when Alexander Peabody’s “oppressive monopoly” was criticized. Today, WSF is both a vital lifeline and a target of criticism, with riders paying fares covering only a fraction of costs while non-users subsidize the system through taxes. The state’s management of the nation’s largest ferry system remains a complex, often underappreciated task.

Conclusion

The Black Ball Line’s introduction of scheduled sailings in 1817 transformed maritime transport, setting a standard for reliability that influenced global shipping and laid the foundation for the Puget Sound Navigation Company. Through the Peabody family’s vision, the Black Ball legacy shaped Washington’s ferry system, which evolved into WSF under public ownership. Today, WSF’s reliance on 43% public funding underscores the enduring challenge of balancing operational costs with public expectations. The Black Ball Line’s pioneering spirit continues to inform modern ferry operations, reminding us that innovation in transport often requires sustained public investment to thrive.

The Black Ball Line’s groundbreaking efforts in establishing scheduled sailings marked a pivotal evolution in logistics services, transitioning from erratic, cargo-dependent voyages to predictable, customer-focused operations that prioritized reliability and efficiency. This innovation not only elevated New York’s status as a global port but also inspired a broader shift in the industry, influencing everything from transatlantic trade to regional ferry systems like WSF. In today’s interconnected world, it remains imperative for all logistics companies: whether in maritime, air, rail, or road transport to continually evolve with technology and innovation, adopting advancements such as AI-driven route optimization, autonomous vehicles, blockchain for supply chain transparency, and sustainable energy solutions to meet escalating demands for speed, sustainability, and resilience in an ever-changing global economy.

More information on current state of WSF.

https://www.seattletimes.com/opinion/wa-state-ferries-far-from-shipshape